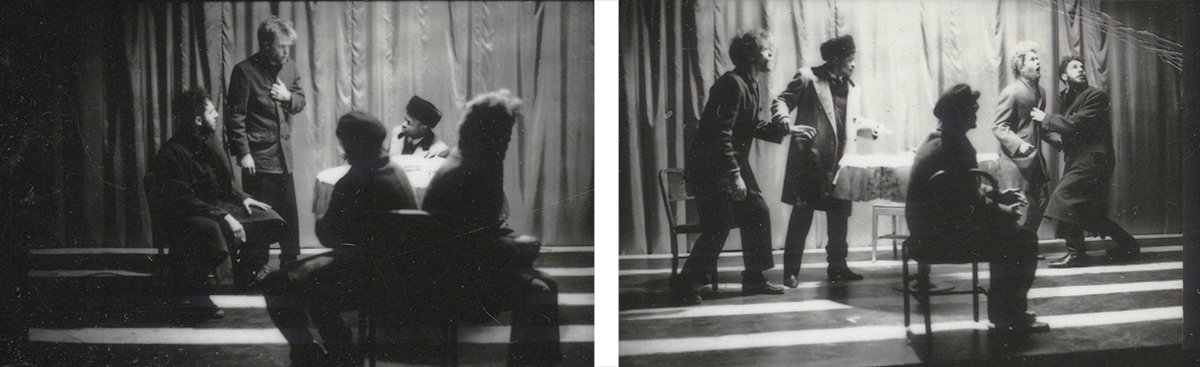

Astonishing: The Devils

The Devils / Adam Danheisser, Michael Dahlen

Photo courtesy of NYU/Tisch Grad Acting Program

It’s very difficult to be surprised in the theatre. Probably because it’s really hard, if not impossible, to invent a new theatre effect. Everything that you see, is a repackaging of something that has been done for a long time. See my article on Six Characters for perspective on that.

The best theatre leaves me awestruck, winded, spinning down an intellectual rabbit hole, or emotionally drained.

If I’m occasionally surprised in addition to all that, it seems like necromancy.

Usually when I’m surprised, it’s because I discover that the Pepsi that I want to buy at intermission costs 15 dollars. Really? I know it comes in a souvenir cup, but…

Or the actor that I expected to see is being replaced by her understudy. (The understudy was great, by the way, but I was still surprised.)

But none of that has to do with what happens onstage.

Sometimes I am surprised by what the playwright does. Kennedy’s Children is a play consisting solely of monologues about the 1960s. I saw it in grad school and I remember feeling gut-punched when Carla (the Marilyn Monroe character), after talking to us for a half an hour, reveals she took a hundred sleeping pills. And that soon after the action of the play - she’ll be dead.

But this is prestidigitation by the playwright.

Here is some director magic.

In 1993, I saw The Devils at NYU, directed by Robert Woodruff.

The Devils / Tim Michael, Catherine Kellner

Photo courtesy of NYU/Tisch Grad Acting Program

Woodruff has a career that spans five decades, and he directed the premieres of many of Sam Shepard’s seminal works. The play was adapted from Dostoevsky’s The Devils (sometimes translated as The Possessed or The Demons), by Elizabeth Egloff, an Emmy-nominated screenwriter and playwright. Egloff did a remarkable job of transforming Dostoyevsky’s 700-page masterpiece into a gripping, charismatic comic-drama. It was subsequently produced by the New York Theatre Workshop under the direction of Garland Wright, but I am going to talk about an arresting moment from Woodruff’s version.

Elizabeth Egloff, playwright and Robert Woodruff, director

The Devils is about the machinations of a group of would-be revolutionists in a fictional Russian town in 1870 and the extreme consequences of their actions in such a torrid political era. It is considered one of Dostoevsky’s masterworks, along with Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, and The Brothers Karamazov.

Fyodor Dostoevsky

The Devils was staged in the NYU black box theatre with the audience on risers on the long side of the room. It had a curtain across the upstage which, when opened, could reveal about seven more feet of space to the back wall. The scenic design was by Greco; costume design by Kaye Voyce, lighting by Kevin Lange and the sound design was by Darron L. West. The assistant director was Carlos Murillo.

The Devils / Tim Michael, Jodi Sommers, Anjaune Ellis

Photo courtesy of NYU/Tisch Grad Acting Program

Woodruff’s staging was frequently abstract, which excavated meaning from deep within Egloff’s rich text.

The Devils / Kevin Isola

Photo courtesy of NYU/Tisch Grad Acting Program

It never works to describe wonderful physical scenes, but here goes.

The Devils / David Costabile, Michael Dahlen, Adam Danheisser, Sean Thomas

Photo courtesy of NYU/Tisch Grad Acting Program

There was an extraordinary comic scene towards the top, which the actors called “five men three chairs,” in which five of the revolutionaries had a meeting to discuss what they were going to do. But because they could not get a chair for everyone, there were only three chairs at the table. If you were sitting in a chair at the table, you had authority. If you were not sitting in a chair, you did not. So the scene became this hilarious dance of musical chairs. Impassioned characters arguing at the table would stand up to fervently make a point, and then another character would quickly steal their seat and usurp their authority. This comic round robin was a perfect joy to watch, as the seated characters found more and more ingenious ways to keep their seats, as the standing ones found more ingenious ways to steal them – all while keeping their debate about what they were planning to do. It was really magnificent.

The Devils / Five men, three chairs

Michael Dahlwn, Sean Thomas, Kevin Isola, David Costabile, Adam Danheisser

Photo courtesy of NYU/Tisch Grad Acting Program

But that’s not what I wanted to talk about.

I want to talk about the staging of the scene in the train car. (There are no photos of this, so you are at the mercy of my imperfect drawings.)

This scene consisted of three actors. The two actors sitting in the train car and man standing reading the paper.

The curtains across the back of the stage parted to reveal this scene, which consisted of the two benches facing each other against the back wall, with a table in between. The two conspirators, Stavrogin and Peter Verkhovensky, faced each other on each bench and the third actor stood downstage of them, reading a paper.

My depiction of the scene.

At the end of this scene the curtain closed and different scene took place in front.

Then the curtain opened, and the same two characters continued their discussion, but this time, from a 90 degree angle.

Another curtain close and another scene in front.

The third time the curtain opened on the train car, we were now LOOKING DOWN on the three actors.

What the what!? The audience hasn’t moved. Now, the actors are all sideways.

Each actor was now SIDEWAYS with their FEET AGAINST THE WALL. The benches were rotated and the actors must have been supported by something to keep them at this angle, because all three actors were above the floor. According to assistant director Carlos Murillo, “The rationale for the ‘overhead shot’ was the reveal that the man reading the newspaper had gotten his throat slit. He was slumped over, a second passenger tilted him back and the cut throat was revealed.”

And they played the scene this way until the curtain closed, and the rest of the play continued.

Seeing this was like getting slapped in the face with a wet towel. I’ve seen a thousand plays and I’ve never seen a director rotate the perspective of a scene like this. What really made it arresting was seeing the first two “normal” scenes, before the third.

Woodruff revealed the inspiration for the staging:

“I had just come from Berlin and saw Heiner Müller do Hamlet and Hamletmachine in about seven hours, the Hamletmachine inserted between the second intermission breaks in Hamlet. He did Ophelia’s grave scene (Alas, poor Yorick) from Ophelia’s POV. So we were looking at people in a circle of half bodies cut into a stage-wide black drop, bent over staring down into the grave - perpendicular to the stage, facing the audience - with a moving clouded blue sky behind them. Awesome.”

Like all great moments of theatrical staging, Woodruff’s train car flip was not a gimmick. And by that, I mean the director thinking, “Wouldn’t it be cool to see them from above?” It’s a great moment because the play is (in part) about conspiracy and its consequences. When the actors are rotated and we are looking down on them, we literally become a fly on the wall – or in this case, a fly on the ceiling – seeing something that should not be seen. For that moment, we ceased to be an audience and were transformed into eavesdroppers catching something extremely dangerous. And consequently we were sucked deep into the play as if through a vacuum tube.

I’ve never seen anything like this before or since.

Robert Brustein said that theatre is the only art form that has the power to astonish us.

Consider me astonished.

Thanks to Robert Woodruff, Elizabeth Egloff, Ann Matthews, Catherine Kellner and Carlos Murillo for their kind and generous assistance with this article.