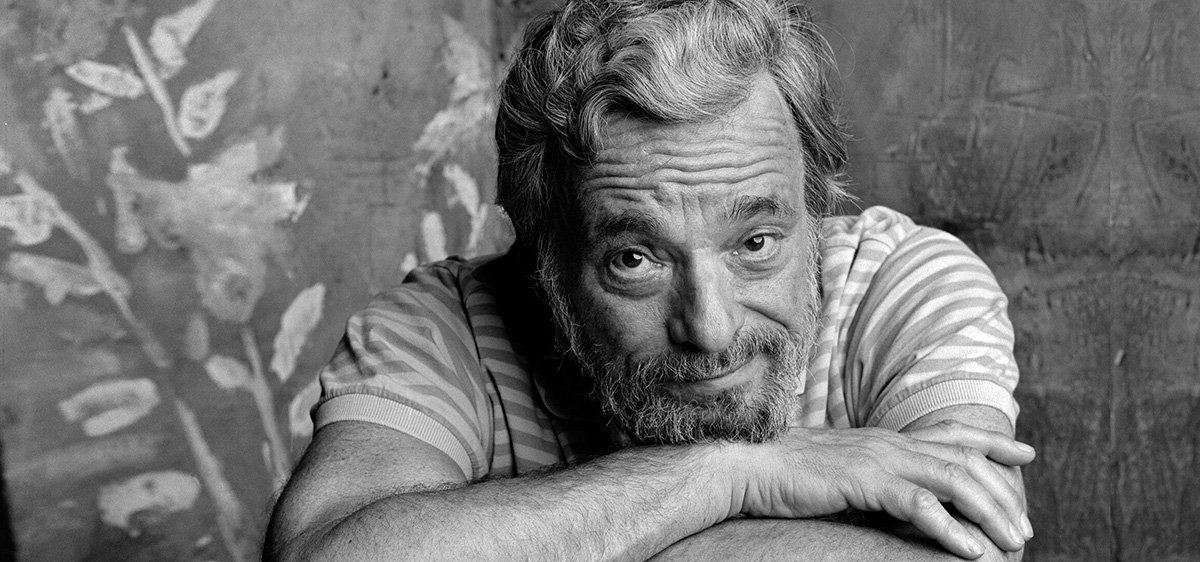

Rhyme and Reason: Stephen Sondheim

It took my breath away on Friday afternoon when I heard the news of Stephen Sondheim’s death. Yes, he was 91, but he wasn’t sick. No one saw it coming.

I was hoping not to have to write about him for another 10 or 20 years.

So it goes.

Stephen Sondheim was the Shakespeare of theatrical lyric and song writing. He took the art form to its absolute apogee. He was in a class by himself.

For a definitive appreciation, see the New York Times obit by Bruce Weber. Equally as good in its own way is Adam Gopnik’s tribute in The New Yorker.

Like a lot of musical theatre nerds, I was a Sondheim geek growing up. The first musical I was in was West Side Story and the first show that I ever directed was A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum.

I regrettably missed many of Sondheim’s musicals when they were on Broadway. Although I did see the original Sweeney Todd twice, and I was able to see Merrily We Roll Along during its 16-performance run. Sondheim and company tried to fix that troubled reverse-chronology musical during its extraordinary 52 previews. But it was not to be. I feel lucky to have seen it.

My friend Jim was on the team that created this graphic. Jim never liked it. He called it “throwing the dog.”

I’ve actually written the book, music and lyrics for one full-fledged musical, The Warrior Queen; and I‘ve written the music and lyrics for dozens of other songs which found their way into my plays. Like everyone else who has ever been mentored by his body of work, I tried (in vain) to emulate him. His work was a model of concision, of technique, and of storytelling.

Sondheim’s composing does not get talked about as much as his lyrics, because frankly, it’s harder to discuss musical compositions in print, as compared to his words. Even in the two books that he wrote, he chose to focus on the lyrics and not the music. But he has written some of the most evocative and beautiful melodies in all of musical theater. “Sunday” from Sunday in the Park with George, which is all over the internet this week, makes me cry for its sheer beauty.

People who write about Sondheim often cite Barcelona from Company as the quintessential Sondheim song because it can be likened to a one-act play. This is easy to see because the song exists as a dialogue between the two characters. And like just about everything else he ever wrote, it takes you somewhere you didn’t expect. Sondheim said that every song is a one-act play. He learned that from his mentor and friend Oscar Hammerstein II.

Although it’s impossible to choose, my favorite Sondheim lyric might be one from A Little Night Music.

Middle-aged lawyer Fredrik Egerman is trying to find a way to consummate the marriage with his 18-year-old wife, who apparently is content to stay a virgin. And he is going through a list of books to read to her which might put her in the mood. But it’s just the books he has in the house and none of them are appropriate for seduction.

Here is the lyric:

In view of her penchant for something romantic

De Sade is too trenchant and Dickens too frantic

And Stendhal would ruin the plan of attack

As there isn’t much blue in the Red and the Black.

Sondheim is writing for a character who knows his library, Stendhal included, so he is not about to explain the books (or the jokes).

Let’s look at just those last two lines. How much is packed into those 19 words?

There is “plan of attack,” a military metaphor related to conquering his wife’s maidenhead, which is drawn from the Revolution of 1830, a topic of Stendhal’s book. Then he makes word play with the colors: “blue in the Red and the Black” with blue meaning “risqué.” There is alliteration of “Blue” and “Black,” which both fall on heavily stressed syllables in the musical phrase. And finally there is that internal rhyme “ruin” and “blue in,” with the added trick that is alway harder to rhyme one word with two words.

And this is just two lines of an entire score. When I heard those lines and really ruminated on them I thought, “Wow, I guess you can make the words do whatever you want.”

If you’re a genius.

Sondheim wrote two books, Finishing The Hat and Look I Made A Hat, where he dissects and critiques all of his lyrics. He is particularly critical of the young Sondheim’s lyrics to West Side Story.

One example is when Maria sings:

I feel pretty and witty and bright!

And I pity any girl who isn't me tonight.

Sondheim says, “with my first professional exposure, I was hungry for any opportunity to show off inner rhymes and trick rhymes.”

He came to see how wrong this clever rhyming was for the unsophisticated character of Maria. “I have blushed ever since,” he said. In the future he was only to give such lyrical acrobatics to characters of high intellect or cleverness. As well as understanding that lyrics not only tell a story, but reveal character.

In the introduction to the books, he spends most of his words making a case for true rhymes. Or, as I like to call them, “rhymes.”

In the Times article, Weber says this:

“He was a world-class rhyming gymnast, not just at the ends of lines but within them — one of the baked dishes on the ghoulish menu in Sweeney Todd was “shepherd’s pie peppered with actual shepherd” — and he upheld the highest standards for acceptable wordplay.”

I am famous in my house for complaining about “rhymes” in songs that don’t quite rhyme.

That’s a lot of assonance.

Assonance noun. In poetry, the repetition of the sound of a vowel or diphthong in non-rhyming stressed syllables.

Playwright Willy Russell makes a joke in the comedy Educating Rita, where the “uneducated” hair-dresser Rita is tutored in poetry by a university professor.

FRANK: Do you know Yeats?

RITA: The wine lodge?

FRANK: No, W.B. Yeats, the poet.

RITA: No.

FRANK: Well, in his poem “The Wild Swans At Coole”, Yeats rhymes the word "swan" with the word "stone". You see? That's an example of assonance.

RITA: Yeah, it means getting the rhyme wrong.

The imperfect and non-rhymes of pop songs is legendary, but what is maddening to me is when the lyricist could have made a rhyme but didn’t.

The hair band Poison sings:

Every rose has its thorn

Just like every night has its dawn.

“Dawn?” Why didn’t he just use the word “morn?”

Here’s one from the group Nine Days called Absolutely (Story of a Girl):

And while she looks so sad in photographs

I absolutely love her - when she smiles.

Now perhaps it wasn’t meant to rhyme. But he didn’t want to end with the word “laughs?” (Then again, maybe he doesn’t love her when she laughs…)

And finally, it not a rhyme issue, but Jason Mraz sings this in the song I’m Yours:

And it's our God-forsaken right to be

Loved, love, love, love, loved.

All through production of that song, I guess no one told Jason that the adjective he meant was “God-given?” “God-forsaken” means “dismal.”

(That Mraz thing has bothered me for years. Thanks for letting me get it out.)

Sondheim is gracious enough to suggest that many of the lyricists who can’t craft an exact rhyme are not untalented, just lazy.

The Golden age of Broadway.

During the golden age of songwriting in America, (AKA The American Songbook) true rhyming was expected. And that was the standard for Broadway. As the Great White Way is continually influenced by pop music, with its juke box musicals, you can see that standard eroding.

True rhyme is such a foundation (and a given) for Sondheim that he uses an entire chapter to make a case for it at the top of Finishing The Hat. Here’s his proposition:

“A perfect rhymes snaps the word, and with it the thought, vigorously into place, rendering it easily intelligible: a near rhyme blunts it.”

And:

“Two generations of listeners brought up on pop and rock songs have gotten so accustomed to approximate rhyming that they neither care nor notice if the rhymes are perfect or not….pop songs have many values, including the immediacy of feeling that X refers to, but specificity of language, a sine qua non of good writing, isn’t one of them.”

At the conclusion of his multi-paged thesis, he says this:

“Using near rhyme is like juggling clumsily: it can be fun to watch and it is juggling, but it’s nowhere near as much pleasure for the audience as seeing all the balls - or in the case of the best lyricists, knives, lit torches, and swords - being kept aloft with grace and precision. In the theatre, true rhymes work best on every level.”

* *. *

I am still hoping to produce and star in that vanity production of Sweeney Todd that I’ve been threatening to do for a decade. Maybe it will still happen. Because when you can sing Sondheim, it doesn’t get any better than that.