Prodigy of Silence: Paul J. Curtis

One of the significant people in my theatre life was Paul J. Curtis, who founded the American Mime Theatre in New York in 1952. “American Mime” is a specific art form that Paul created, taught, and performed with his company. This was not a theatre of pantomime, (where performers handle the air in such a way as to create illusions) but a specific kind of non-speaking theatre. Paul said that if he knew the confusion that calling it “mime” would cause later, he might have named it something different. He described it as acting and moving at the same time.

Please know that as I use the phrase “American Mime,” that I am not talking about “mime” (silent performing) in general, but Paul’s specific performance form, which he created and developed for over a half a century.

There is so much to say about American Mime that I can’t possibly go into everything here. It is impossible to describe, and so I will mostly be talking about Paul - his personality, his influence, and his particular genius. Like everything else I write on these pages, I will read it over and think, “wow, these paragraphs are the definition of insufficient.”

Paul J. Curtis, Founder and Director of The American Mime Theatre.

Photo by Jim R. Moore

I first studied American Mime when I was a grad student at Cornell. Paul (or sometimes a member of his company) would come up to Ithaca from New York once a week and we would have the class on Friday afternoons. This class consisted of not only the grad students, but also undergrads, as well as students from Ithaca College.

This class was notorious at Cornell. Probably because it was so difficult and it seemed weird to us kids. And before I began, no one who had previously taken the class would talk about it. They would just say, “You’ll see.” In retrospect, I don’t know how many of the students “got it.” But I think most of them committed to it.

In brief: At Cornell, the 23 of us in the class all wore black leotards and tights and the class was structured in two parts. First, there was an 11 minute “prep,” which was designed to get us into a creative state. And then after that there were a series of exercises which were acting-moving focused. “The Prep” was an incredible tool. So incredible that I borrowed it and used to for years and years with my own company. (I will talk about The Prep separately, sometime in the future. It’s amazing.)

Everything in the art form is codified. There are long lists of terms and each term has a precise definition. This was a refreshing change from the entire rest of the theatre world which only had jargon. A word like “stylization” could mean one thing to one director and something different to another. Not so with American Mime. You knew precisely what everything was called what everything meant. (even if you couldn’t do it.)

“Hurly Burly” is one of their signature pieces. It is a vaudeville about three characters, each trying to protect his privacy while occupying a stool barely big enough to contain one of them. The American Mime Theatre, “Hurly-Burly” Rick Wessler, Paul J. Curtis, Charles Barney / Photo by Jim R. Moore

Paul was very intimidating to us. He had a dour demeanor at Cornell. He rarely smiled. He smoked Tiparillos as he sat behind a desk and critiqued our exercises. Yes, that’s right: he smoked cigars during a movement class.

One of the exercises we had to do, which was always terrifying, was called “Moving to Words.” Paul would sit at one end of the room and one by one we would go up to him and, without speaking, we had to try to change his feelings. What does that mean? Well, we would try to make him laugh, startle him, scare him, relax him, or any other playable action that we thought we could achieve. All without speaking or touching him. And we had to do this through a specific physical form. It was rare that anyone could ever do this. Normally it would go like this:

Student: (doing some crazy gesture in front of Paul)

Paul: What are you doing?

We normally weren’t allowed to speak, but we could answer a question.

Student: I’m trying to intimidate you.

Paul gives him a worn, withering look, and takes the cigar out of his mouth.

Paul: Listen. I’m 54 years old. I don’t intimidate easily. Did you really think you could intimidate me?

Puts the cigar back in his teeth and glares at the student.

And the student would slink away, himself intimidated, and the next sitting duck would approach.

Another Student: (doing another crazy gesture in front of Paul)

Paul: What are you doing?

Student: I am trying to surprise you.

Paul: Listen, kid. Unless you can levitate, nothing you can do will surprise me.

The American Mime Theatre / Paul J. Curtis teaching Technique in his New York City Studio. Photo by Jim R. Moore

I loved American Mime. I loved it because it was acting and moving at the same time. I’m not a mover by any stretch of the imagination, but I liked that idea. Absolutely real spontaneous feelings expressed through a rigorous form. Sounds impossible. Paul called it “falling out of a window and looking good on the way down.” This idea would inform most of my directing and playwriting from then on.

American Mime made such an impression on me that when I left Cornell, I went to New York to study with Paul at his Bond Street Studio. In total, I studied with him for about three years. I got to know him personally and discovered that his taciturn manner was only a professional demeanor. He was very warm and caring - and decent. And “decency” was not in fashion in the theatre world of the 1970s and 80s. I learned an immense amount under his mentorship. And his view that theatre is as physical as it is emotional changed the way I looked at performance all together.

Like any great art form, we were not being taught American Mime to have a career in it, necessarily. We were taught the principles embedded in it so that we could then apply them to any creative performance.

“The Lovers” The American Mime Theatre, Paul J. Curtis and Anita Morris.

Photo by Tom Yee

It was so refreshing and unique to have a class where you were taught the physical and emotional aspects of performing at the same time. In both grad schools where I studied, you either learned acting, or you learned moving, depending on the class.

Paul also stressed playing the long game. He used to say, “It can take you one or two years to find something that works.” This was unusual advice for students who were used to having only a few of rehearsals to “come up with something.” Paul felt that most students of the performing arts lacked the motivation to achieve proficiency. And that the price of progress in acting was simple: intense and continued effort.

“The Unitaur” Joseph Citta in the center, Erica Sarzin on right

Erica Sarzin was the leading lady of the American Mime Theatre during the time I was studying. She was one of the performers through whom I was able to see the art form at its most fully realized form. Like Ryszard Cieslak for Grotowski, Sarzin, to me, was the embodiment of American Mime.

And one last thing for today:

Paul said that one of the most precious things that an actor could possess was freedom. Freedom was the ability to be completely uninhibited while acting. To be able to perform as if no one was watching, while everyone was watching. Freedom was necessary to successful performing, but actors could lose freedom at any moment for a number of reasons – distraction, making a mistake, emotions drying up, your mother is in the audience, etc. So he created the idea of the “Freedom Device.” The Freedom Device could be anything that you can do which allows you to regain your Freedom. And to be specific, a “Device” was the opposite of “trying.” Anyone could “try” to do anything. What you wanted was something concrete with prevented you from doing it the old way, which was no longer working. That’s a “Device.”

In that vein, Paul said that if, in rehearsal, a teacher or director ever inhibited you by calling out a “mistake” you made, you should kneel in front of them and declaim, “Here’s my head. Take an ax. Chop it off.”

I don’t know if that comes across as funny in print. But it was hilarious when he demonstrated it.

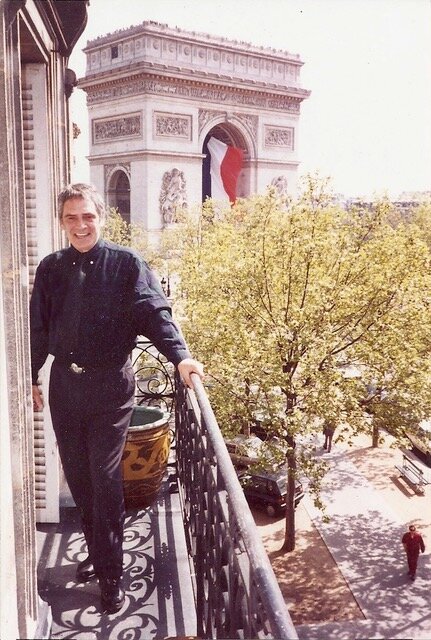

The American Mime Theatre, Paul J. Curtis in Paris to teach “American Mime” to actors and dancers

Paul died in 2012 at the age of 84. Like Tadeusz Kantor, or Pina Bausch, or any other genius who ran a company that they founded, the company is profoundly affected by his passing.

But he taught for 60 years and I am proud and lucky to be one of the people who he taught.

•••

The American Mime Theatre still teaches and performs. Here is their website: