I did not see Brook's "Dream"

I did not see Peter Brook’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

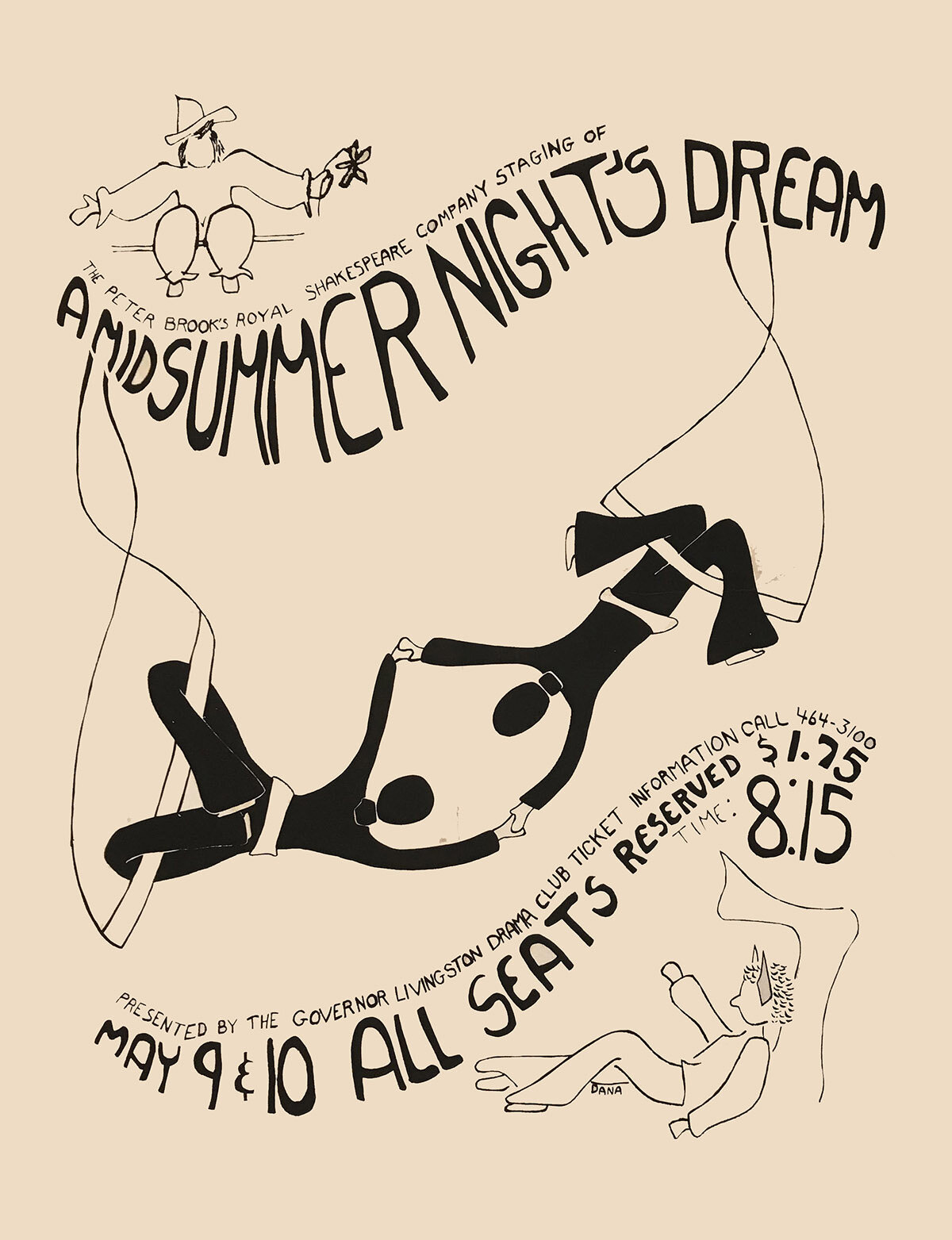

But I did see this high school production.

Peter Brook in the 1970s

Brook’s seminal production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1970 changed the way Shakespeare was to be directed, staged and viewed from then on. Books have been written about this production. It has been called the single most influential theatre production of the twentieth century, Shakespeare or otherwise. When it premiered, the Sunday Times reviewer said that it was, “the sort of thing one only sees once in a lifetime, and then only from a man of genius."

It is hard to go back in time and imagine theatre BEFORE this Midsummer, because its thumb print is on everything we see. Before Brook, there had been a long tradition of Midsummer Night’s Dream in England which did not stray far from the English fairies. Here are some examples:

Vivien Leigh as Titania 1937 at the Old Vic.

Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree’s Midsummer, 1900

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Hollywood Bowl, 1934

Here is a still from Brook’s production.

Oberon (Alan Howard) Titania (Sara Kestelman) and Puck (John Kane)

Courtesy of the RSC / Photo by Reg Wilson © RSC

It featured no classical Athens, no magical forest, but a white box (designed by Sally Jacobs). Not only did the costumes of the fairies not in any way represent fairies, they didn’t seem to represent anything else in particular either. The fairies used stilts, swung on trapezes, spun plates on sticks and looked down on the action from the top of the white box.

I quote from the New York Times review of the show in 1970:

“Once in a while, once in a very rare while, a theatrical production arrives that is going to be talked about as long as there is a theater, a production that, for good or ill, is going to exert a major influence on the contemporary stage. Such a production is Peter Brook's staging of Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, which the Royal Shakespeare Company, introduced here tonight…Brook has approached the play with a radiant innocence. He has treated the script as if it, had just been written and sent to him through the mail. He has staged it with no reference to the past, no reverence for tradition…He has stripped the play down, asked exactly what it is about. He has forgotten gossamer fairies, sequined eyelids, gauzy veils and whole forests of Beerbohm trees…It is a magnificent production, the most important work yet of the world's most imaginative and inventive director. If Peter Brook had done nothing else but this ‘Dream,’ he would have deserved a place in theater history.”

It is not merely that Brook did Midsummer in a way that it had never been done before. Although that’s true. The remarkable thing about Midsummer Night’s Dream was that he did not try to represent anything. Be he tried to evoke everything.

The play is about magic. But what is magic? Is it actresses with wings? No, that has just been representing magic. Brook said, in effect, I am not going to represent magic, I am going to create magic.

Titania (Sara Kestelman) and Bottom (David Waller), with four lovers sleeping on trapezes.

Courtesy of the RSC / Photo by Reg Wilson © RSC

Brook explains his inspirations: “The first visit to Europe of the Peking Circus revealed that in the lightness and speed of anonymous bodies performing astonishing acrobatics without exhibitionism, it was pure spirit that appeared. This was a pointer to go beyond illustration to evocation.”

He goes on: “A year later, in New York, it was a ballet of Jerome Robbins that opened another door. A small group of dancers around a piano brought into fresh and magical life the same Chopin nocturnes that had always been inseparable from the trappings of tutus, painted trees and moonlight. In timeless clothes, they just danced. These pointers encouraged a burning hunch that, somewhere, an unexpected form was waiting to be discovered.”

Oberon (Alan Howard) and Puck (John Kane) above and Demetrius (Ben Kingsley) and Helena (Frances de la Tour) below.

Courtesy of the RSC / Photo by Reg Wilson © RSC

This is the legacy of Brook’s Midsummer Night’s Dream. which is everywhere to this day. It is that you could do a play, and successfully, evocatively, without trying to represent what is in the script.

Here are some photos of recent productions, Shakespeare and otherwise. Without the caption, it is impossible to say for sure what the show is. Whether the production succeeded or not I can’t say. But this non-representation is now an inexorable part of our theatre language.

Titania and fairies in Midsummer Night’s Dream, 2019

Courtesy of Nevill Holt Opera, Leicestershire, UK

Lady Macbeth and witches in Macbeth, 2019

Courtesy of Royal exchange Theatre, Manchester, UK / Photo Credit Johan Persson

A Streetcar Named Desire, Berliner Ensemble, 2019

Courtesy of the Berliner Ensemble / photo credit: Matthias Horn

FYI – Brook was adamant about NOT filming the production for posterity, (although some individual scenes were filmed) and the cast agreed on it. He thought the essence of the production could not be captured on film. They were subsequently asked to tour to Japan, but they could not arrange it. So he did film the entire play it so that it could run on Japanese TV, with the stipulation that the print be destroyed (in the presence of the British Consul!) after it was televised. Sometime after the airing, Brook had second thoughts and decided that he DID want to have a record of the show. So he called the television network in Japan in order to ask them to save the film. But it was too late. The Japanese told him proudly that his wishes had been carried out and the print had been destroyed.

•••

Which leads me to this high school production, which was the first live production I saw of any Shakespeare play.

I had seen Midsummer on TV on PBS, when I was ten. (Diana Rigg as Helena, Helen Mirren as Hermia and a 34-year-old Judi Dench as Titania!) That might have been my first experience with Shakespeare at all. I also think I had seen the 1935 movie with Mickey Rooney as Puck. So I knew what it was “supposed” to look like.

Governor Livingston High School was not my high school, but it was in the same school system. I took drama classes there every summer, because their theatre teacher, Norman L. Schneider, was so exceptional. So what did he do with the play?

In 1974 Brook published an authorized acting edition of his production and made it available for any company who wanted to do it. This was the version that Schneider used for his high school show, the year after it was published. But “authorized acting edition” - what does that mean?

It meant that if you leased the acting edition, you could do Brook’s staging of the show. You could build his white box set exactly as it was, you could recreate his costumes and properties exactly, and you could block it and stage it exactly as he staged it. It contained diagrams of the set and drawings of the costumes and notated all of the blocking in detail. You could even use the music that Brook used. The book showed you how to replicate Brook’s production exactly, if you wanted to.

The edition states on page one: “This unique staging and production can provide the basis for your own production upon payment of the royalty fee.”

It was a recipe book for Brook’s version of the show.

Now, as Grotowski said, “All recipes lead to banality.”

That may be true and it also seems contrary to the investigative impulse which animated Brook’s Midsummer in the first place.

Check out that $1.75 ticket price. That was the going rate for a high school show.

But Schneider was very talented director. He used trapezes, but scaffolding stood in for Brook’s white box. Above that, I don’t recall how much he used or didn’t use. But, I do recall to this day that his production was incredibly ALIVE. I remember being surprised and thrilled at every turn. It was nothing like what I was expected. The production also featured singers, dancers, and their high school gymnastics team doing acrobatics. Although I knew it was rehearsed, the whole thing seemed improvised in a way that made it appear like it was happening for the first time. It was a spectacular introduction to Shakespeare on stage.

Governor Livingston High School senior Donna Serido as Puck on trapeze, scaffolding behind. 1975

Donna Serido, who played Puck, remembers the production: “As a teen I didn’t realize just how “cutting edge” Mr. Schneider was as a director. I was lucky to be at the right place and the right time to experience such a gifted man. I didn’t take pictures…but I did learn how to spin plates.”

I can imagine that after the only existing film of the show was destroyed, that Brook wanted there to be some record of the show. Some way for the show to live on. And the acting edition was a possibility for that. This was the early 1970s and Brook wanted to spread the gospel of non-representative Shakespeare. I don’t know how many other groups took him up on it. But this production was an amazing confection.

Yes, it is a recipe book. But it also depends on who the cook is.