Pepper and Pirandello

Nicholas Hytner, the former Artistic Director of the National Theatre in London, said that you can’t have an idea that someone hasn’t had before. He was talking about Shakespeare at the time. But it’s true for all theatre. And, as a director, I find that kind of comforting. It means that long before we came along, there were theatre people doing their jobs with a vengeance.

Sometimes you have an idea on your own, only to discover that, no, it’s been done. That’s usually the case. But occasionally, a theatre deliberately re-introduces some great, forgotten stagecraft to the audience. Such was the case with the American Repertory Theater’s famous production of Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author, directed by Robert Brustein. Michael Yeargan was the set designer, and Jennifer Tipton was the lighting designer. Six Characters was one of their signature pieces in the 1990s and they toured the world with it.

This production contained several magical effects but I’m going to talk about just one. What made it extraordinary – and this is why I love theatre – is that seeing how it was done didn’t lessen its impact. (Thank you, Mr. Brecht.)

A.R.T. Six Characters in Search of an Author

Monica Koskey, Benjamin Evett, Marianne Owen, Joseph Pasquale, Nicole Pasquale, David Ackroyd.

Courtesy of the American Repertory Theater / Photo: Richard Feldman

What they did was a version of “Pepper’s Ghost.” Although it was a standard bit of stage illusion in the Victorian Era, Pepper’s Ghost is now largely unknown. In 1862, civil engineer Henry Dircks invented a clever-but-impractical ghost effect and the scientist John Pepper found a way to adapt it easily for the theatre. When they premiered it, the sight of ghosts appearing and disappearing onstage was stunning and miraculous. The “Ghost” became so popular that in its initial showing in London, a whopping quarter-million people saw it over the course of 15 months. Pepper then licensed the effect so that every theatre in London and beyond could do a version of the Ghost if they wanted to.

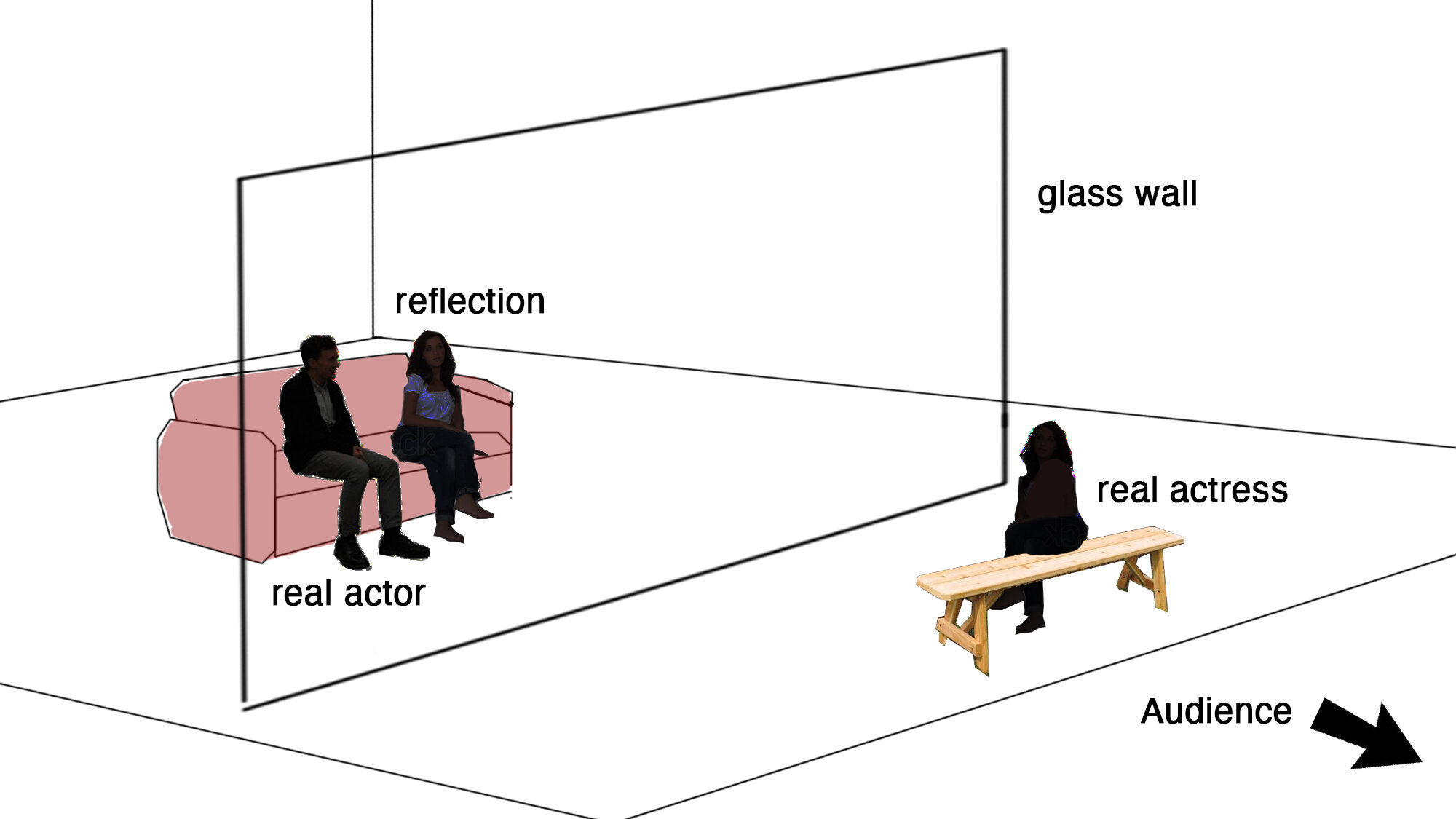

The Victorian version involved a large glass wall on the downstage edge of the stage which was tilted at an angle towards the audience. Actors in the orchestra pit, unseen by the audience, could seem to interact with live actors on stage when they were lit and were reflected through the glass wall. It is important to understand that the reflections did not appear on the glass but on the other side and were three-dimensional - like holograms.

The stage lights were dim, and so the audience did not know that the glass wall was there. When working properly, these orchestra pit actors were indistinguishable from the live actors on stage, and their reflections shared the stage with them. It is like when you are looking out your window at night, and your reflection in the glass looks like it is standing outside. In the Pepper’s Ghost effect, when the light on the reflected actor was turned off, they miraculously disappeared from the stage.

Of course, the Pepper’s Ghost plays, as historically performed, were short pantomimes. They had to be. The real onstage actor could not be heard behind the sealed glass wall. And if the Ghost actor’s voice was heard coming from the orchestra pit instead of the stage it would ruin the illusion. “Scrooge and Marley” and “Hamlet and the Ghost” are just two of the short pieces that were regularly performed.

Now to the A.R.T.

And Spoiler Alert: there are no photographs of this moment, because it did not photograph well. So I am going to do what they used to do at the Royal Scientific Society of London: I am going to explain it.

To remind you, here is the synopsis of the play as the A.R.T. puts it: “Six characters crash a theatre rehearsal searching for an author and a stage to put an end to their tortured story. Reality and illusion are repeatedly tested, as the characters, despite resistance from the acting company, seek to prove that their drama is more real than any dramatic fiction.”

A.R.T. Six Characters in Search of an Author / mirrored glass wall, hiding the upstage Monica Koskey, David Ackroyd, Jeremy Geidt.

Courtesy of the American Repertory Theater / Photo: Richard Feldman

The “Characters” in this production were dressed in early 20th century black and white costumes with whitish face make-up, reminiscent of a silent film. The “Actors” whose rehearsal they crashed played themselves and were all members of the ART’s resident company at the time. And they were rehearsing a play that was actually in the repertory. Brustein adapted the script and put the “Actors” in the here and now, rather than keep them in the 1920s Italy of the original text. Of course, in the 1921 production, the Italian actors were in the here-and now. Brustein’s updating seemed natural and was one of the things that made this show work especially well.

In the course of the play, the “Characters” are telling their story in order for the ART “Actors” to learn it. And particularly the scene where the pimp Emilio Paz tries to convince the Stepdaughter to prostitute herself.

In the ART production a sheet of mirrored glass was brought down in the center of the stage parallel to the proscenium. For most of the play it was a mirror (see above photo). At the appointed time, light comes up upstage of the glass and it becomes transparent (much like a scrim) and we see the room of Emilio Paz. There is a large couch center and the real actor playing Paz is sitting on this couch, ten feet upstage of the glass wall.

The Stepdaughter sits on a simple bench, ten feet downstage of the glass wall, and she faces upstage. When she is lit her image slowly appears on the couch next to Paz. As the scene plays, we are not watching the real actress, (we could if we wanted to, but we’re not) but we are looking through the glass to watch her reflection, which is sitting next to Paz. In the light, both Paz and the Stepdaughter’s reflection seem absolutely corporeal.

But what elevated it to something sublime and astonishing was the painstaking choreography between the two actors, which allowed a man and a specter to interact in the same space. We would see Paz take the Stepdaughter’s hand. We would see him touch her hair and she would pull away. And we would see him slap her and watch her recoil. I know how difficult it is to produce physical and emotional work of this exactitude. The actors sold this interaction, even though they were actually 20 feet away from each other and separated by glass. When the lights faded on the real Stepdaughter downstage, she evaporated and disappeared from Paz’s room upstage.

This effect had its full impact because the entire play is about characters from two different realities occupying the same space – the fictional Characters and the real-life Actors. If it had not been, this effect would have just been a trick – a magic trick – with little or no resonance. As it was, it became a touchstone, not only of the play but of Theatre itself.

I don’t know where the idea for this originated in this production - but again, Robert Brustein was the director, Michael Yeargan was the set designer and Jennifer Tipton was the lighting designer. I’ve never seen anything like it before and I’ve never seen anything like it since.

It is so thrilling when I see something in the theatre and think, I didn’t know you could do that on stage. It doesn’t happen often, but when it does, it lodges permanently in my imagination.